“A World in Your Ear” by Richard Miron, member, journalist and podcaster

In a former professional existence, I was a BBC foreign affairs reporter. I spent a number of years based in the Middle East, but upon returning to London I became one of a number of reporters who was deployed to various international destinations to cover the news stories of the day. In late 2001 following 9/11, I was dispatched by the BBC to Afghanistan to report on the situation in the country after the Taliban had been routed. I’d never been to Kabul and had little direct knowledge of that part of the world. My role was to regurgitate news of what was happening on the ground – and thankfully little in-depth analysis was required.

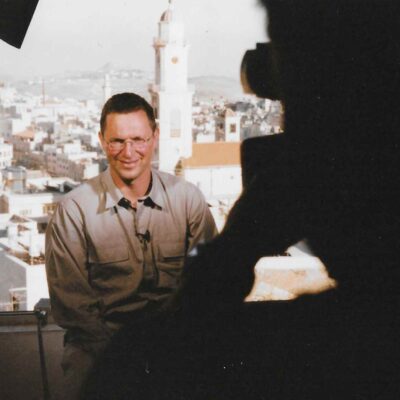

In the parlance of broadcast journalists, I was a ‘dish monkey’ – one of a number of correspondents to stand on a roof surrounded by satellite dishes and broadcasting ephemera. My job was to stare into a camera lens against the backdrop of Kabul talking to various news presenters back in London with the latest from Afghanistan beyond the confines of my rooftop.

When on shift I couldn’t stray far from my broadcasting position, as I required to be on air at least a couple of times an hour. This meant that information was handed to me by a producer or a local translator who would monitor what was going on in the world outside. This was made all the more challenging by the patchy internet connections and unreliable phone networks.

One day during a shift while standing on the roof I was informed by London of a report that a senior Taliban leader had been spotted in the north of the country.

‘But I don’t know anything about it,’ I responded to the news editor who was sat in TV Centre in Shepherd’s Bush.

‘So, we’ll tell you what we have, which is a report from a Pakistani news agency and you can take those details and work with them,’ he responded.

What then followed was me being read the agency material into my earpiece, and then going on air a few minutes later to relay back to London the latest from Afghanistan.

This anecdote illustrates some of the contorted ways in which the news sometimes came to be told – although in fairness it was ordinarily much more thorough than my Afghanistan experience.

Reflecting on that story, I find it has resonance for working in the media in the time of Covid-19. I now run a consultancy that provides advice, training and production services to organizations that want to use podcasts. During normal times, presenters sit with interviewees or travel to differing locations to record material. That is of course now impossible. But necessity has forced us to innovate, so we can still make programmes while also ensuring social distancing.

Just last week, I found myself driving to South London to drop off a disinfected tape recorder outside the home of a presenter. The plan was for him to connect with an interviewee on the phone who also had a tape recorder. They would both then simultaneously tape their sides of the conversation on the recorders. The material was then to be sent via the internet to a producer (who was socially isolating) and mixed so that presenter and interviewee sounded as if they were sitting next to each other. The process worked smoothly, and I duly received back the freshly disinfected tape recorders in the post. I am also working on another series where contributors are recording comments on the voice memo application of their phones and sending it to a producer to be collated for inclusion in a programme.

We are all adapting to strange new ways of living and working. But in this technological age with broadband, digital tape recorders, Zoom, Skype and much else besides, my professional existence has been fortunate in finding a relative straightforward way to adapt and continue.

This crisis is shining a further light on the utility of podcasts. Organizations are using them in place of live events like seminars and conferences. They are also being put out as a means of communicating to scattered work forces. The technology has enabled audiences to hear programmes on demand in differing locations irrespective of the presence of borders, transmitter locations and more besides.

The coronavirus crisis has in this immediate phase changed a huge amount about the way in which we function. When it has passed, the effects will be long felt in various ways. In the media world, it will likely accelerate the way in which we work, making it routine to use diverse and separate resources to get the job done. Producers, presenters and interviewees will as a matter of course sit hundreds or thousands of miles apart. It will also enable listeners to access a vast array of material whenever and however they choose.

At this time of social isolation podcasts are proving they truly are the ‘audio campfire’ around which we can gather both as programme-makers and consumers to exchange experiences and knowledge. The power of the human voice is proving itself as an important and reassuring presence in these uncertain time.

Richard Miron is the founder and CEO of Earshot Strategies, a London-based podcast consultancy.